Update: Since this article was posted in November 2014, the FCC voted (February 26, 2015) to enforce net neutrality rules that ban paid prioritization.

As the debate over net neutrality rages, two papers co-authored by

Vishal Misra have been recently reprinted in a

special IEEE issue on net neutrality. Both papers examine the economics of the Internet. The

first (from 2008) looks at how profit-motivated decisions by the ISPs work against customers’ preferences for fast Internet speeds at low prices; it also predicted the rise of paid peering, which plays a central role in today’s net neutrality debate. The

second (from 2012) shows how the introduction of a public-option ISP works to align the interests of both customers and ISPs, in the process achieving a free, open Internet without regulation.

Understanding the economics of the Internet is crucial to understanding how best to maintain a free and open Internet—the stated goal of net neutrality.

The connection between Internet economics and net neutrality is not well understood, partly because net neutrality is considered more of a legal and regulatory issue, and partly because the Internet, a vast maze of inter-connected networks, is hugely complex. Economists themselves when analyzing Internet economics fail to take into account the complexity and instead rely on abstractions that simplify traffic flow, routing decisions, and the impact of congestion, and as a consequence fail to account for how the profit-driven decisions negatively affect Internet service for customers.

To bring a more networking angle to the economic analysis,

Vishal Misra with his colleague

Dan Rubenstein and their student

Richard T. B. Ma (now Assistant Professor with the School of Computing, National University of Singapore) along with collaborators Dah-Ming Chiu and John Lui in Hong Kong set out in 2008 to realistically model the way Internet service providers (

ISPs) interact with one another, looking particularly at the pricing policies used by ISPs to compensate one another for transit services. Their findings are described in

On Cooperative Settlement Between Content, Transit and Eyeball Internet Service Providers, which used sophisticated mathematical modeling to accurately depict the complex interactions among different ISPs. Originally published in 2008, the paper obtained new insights into ISPs’ routing decisions and the settlement (payment) among different ISPs, showing the inevitability of paid peering and the incentives supporting it. This prediction made in 2008 is now coming true and is central to today’s heated debate on net neutrality. This paper (one of two co-authored by Misra) was republished by the IEEE in a special

net-neutrality issue that appeared in June 2014.

From symmetry to asymmetry

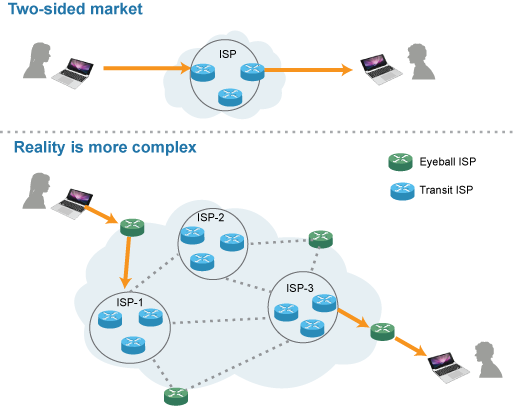

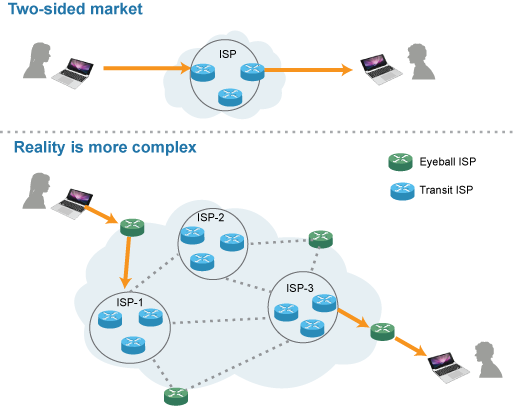

One main goal of the paper was to more realistically model the interactions among ISPs. Economists have typically analyzed and modeled the Internet as a two-sided market, with consumers on one side and content providers on the other, and a single ISP sitting in the middle serving them both. The reality even in 2008 was far more complex, with packets traveling through several ISPs before reaching the intended destination.

With mathematical models providing a more realistic picture of the Internet, the authors use game-theory economics, specifically

Shapley values, to understand the optimal arrangement under which each ISP is incentivized to contribute to the overall good. This methodology showed how in the early Internet, the flow of traffic (mainly emails and files) was roughly symmetrical. A packet originating at ISP-A and handed off to ISP-B for delivery would be balanced by a packet moving in the opposite direction. ISPs often entered into no-cost agreements to carry one another’s traffic, each figuring that the amount of traffic it carried for another ISP would be matched by that other ISP carrying its own traffic. Network neutrality prevailed naturally since ISPs, compensated for bandwidth used, did not differentiate one packet from another. The more packets of any kind, the more profits for all ISPs, an economic situation that aligned nicely with customers’ interest in having an expanding supply of bandwidth.

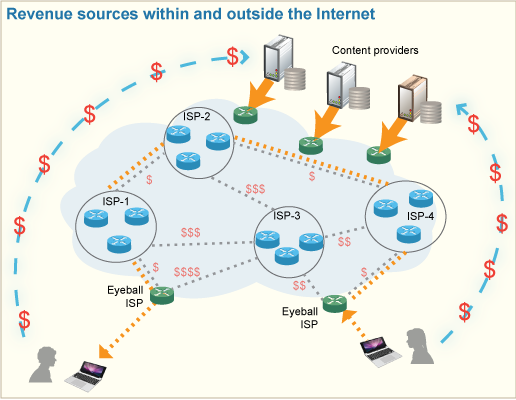

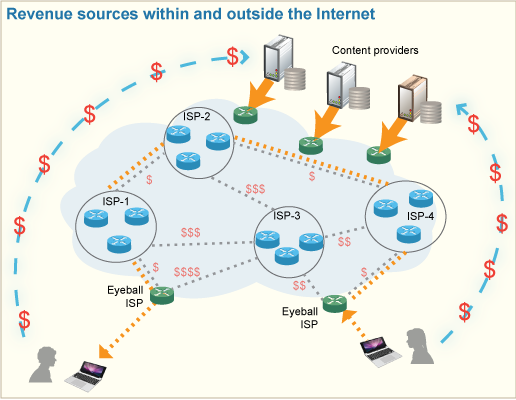

Internet economics have changed considerably in recent years with the rise of behemoth for-profit content providers such as Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Netflix. Their modeling shows the appearance of these for-profit content providers did two things: it changed the Internet from a symmetric network to an asymmetric one where the vast preponderance of traffic flows from content providers to customers. And it introduced a new revenue stream, one outside the Internet and generated by advertising, online merchandizing, or payments for gaming, streaming video, and financial and other services. (Revenues from online video services alone grew 175% from $1.86 to $5.12 billion between 2010 and 2013. Source:

FCC NPRM on the Open Internet.)

The ISPs themselves were changing and becoming more specialized. The paper subdivides ISPs into different but overlapping conceptual types, the main ones being eyeball ISPs such as Time Warner, Comcast, and AT&T that specialize in the last-mile content delivery to paying consumers, and the transit ISPs such as Level 3 and Cogent that own the global infrastructure and provide transit services for other ISPs. Where eyeball ISPs serve people, transit ISPs serve the content providers and earn revenue by delivering content to consumers on behalf of the content providers. Since transit ISPs don’t have direct access to consumers, they arrange with the eyeball ISPs for the last-mile delivery of content to customers.

ISPs are cut off from the growing revenue source happening outside the Internet. The resulting imbalance in profit sharing reduces the investment incentives for ISPs to build out the network.

According to Misra, “In a coalition where one participant doesn’t feel adequately compensated or at least compensated to the same degree as other participants, this gives rise to conflict. Mathematically, we call the situation being outside the core, where some participants have the incentive to leave the coalition since they will be better off without it. In schoolyard parlance, it is the equivalent of taking your ball and going home. “

With an imbalance in the direction of traffic and no mechanism for appropriate compensation, the previous no-cost (or zero-dollar) bilateral arrangements broke down and were replaced by paid-peering arrangements where ISPs pay one another to carry one another’s traffic. Each ISP adopts its pricing policies to maximize profit, and these pricing policies play a role in how ISPs cooperate with one another, or don’t cooperate. Profit-seeking and cost-reduction objectives often induce selfish behaviors in routing—ISPs will avoid links considered too expensive for example—thus contributing to Internet inefficiencies.

Paid-peering is one ISP strategy to gain profits. For the eyeball ISPs that control access to consumers, there is another way. Charge higher prices by creating a premium class of service with faster speeds. Creating a two-class system is currently prohibited by network neutrality; however the FCC proposed in May new rules that would allow such a two-tier Internet, effectively ending at least one aspect of net neutrality: prohibiting the discriminations on delivering different contents on the network.

An imbalance of power

The eyeball ISPs, however, are in a power position because, unlike transit ISPs, eyeball ISPs have essentially no competition. Misra cites data released by FCC chairman Tom Wheeler showing that more than 19 percent of US residents have no broadband provider offering 25Mbps service, and another 55 percent have only one such provider. The ISPs that provide decent-speed service, for all intents and purposes are monopolies. While wireless Internet (including Wi-Fi) is often cited by ISPs as competition, the comparison is not fair. Unwired Internet is not fast as the wired service that is available only through the eyeball ISPs.

Content providers like Netflix are in a much weaker position than the eyeball ISPs. Content providers need ISPs much more than the ISPs need them. If Netflix were to disappear, other streaming services would rush to fill in the gap. For the ISPs, it matters little whether it’s Amazon, Hulu, or another service (and worryingly, services run by the eyeball ISPs themselves) providing streaming services.

If ISPs don’t need Netflix, neither do customers. Customers unhappy with Netflix’s service can simply choose another such service. They can’t, however, normally choose a different ISP.

The monopolistic power of the eyeball ISPs may soon be made stronger. The proposed Comcast takeover of Time Warner would create a single company that controls more than 40% of the US high-speed Internet service market. Anti-trust legislation would seem to prohibit such a takeover, but both companies argue that they don’t compete. In this they are correct. The markets in which Time Warner and Comcast operate do not overlap. Seemingly by design, Comcast operates in San Francisco and Time Warner in Los Angeles, while Time Warner operates in New York City and Comcast in Philadelphia. Comcast Chairman and CEO Brian L. Roberts uses this argument to support his company’s takeover of Time Warner, but Misra sees it differently. “Time Warner and Comcast claim they are not killing competition because they don’t compete in the same markets. That is not an argument; that is a question. Why aren’t they competing?”

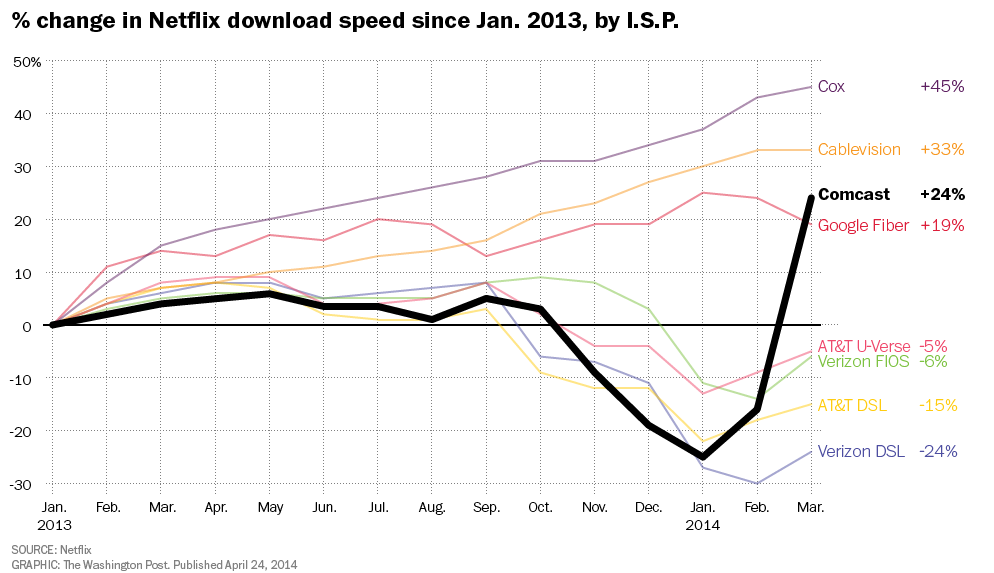

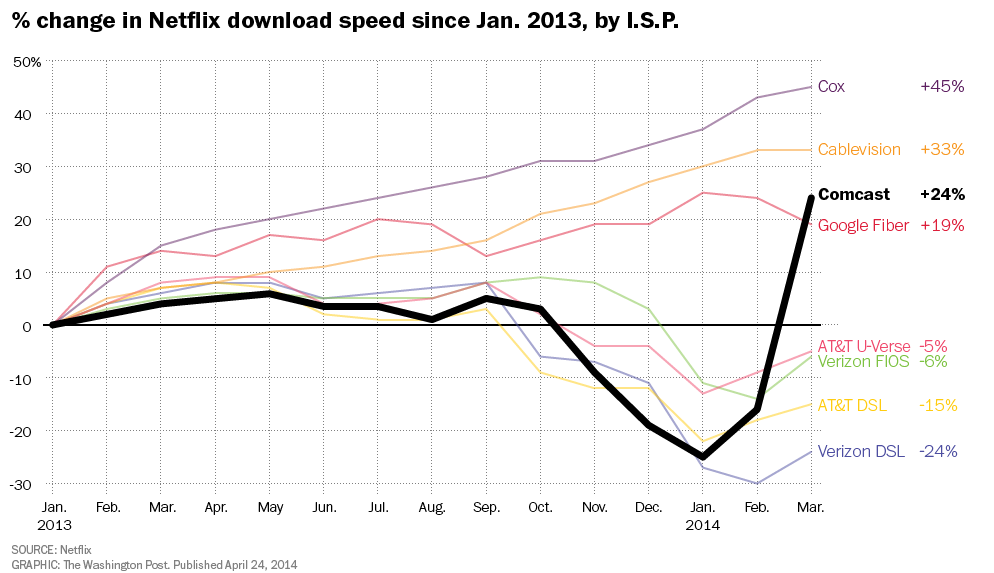

Occupying a position of power and knowing customers are stuck, the eyeball ISPs can and do play hardball with content providers. This was effectively illustrated in the recent Netflix-vs-Comcast standoff when Comcast demanded Netflix pay additional charges (above what Netflix was already paying for bandwidth). When Netflix initially refused, Comcast customers with Netflix service started reporting download speeds so slow that some customers quit Netflix. These speed problems seemed to resolve themselves right around the time Netflix agreed to Comcast’s demands. (Netflix has since signed a similar deal with Time Warner so that Netflix now has special arrangements with the four major ISPs, including AT&T and Verizon.)

It would have been relatively inexpensive for Comcast to add capacity. But why should it? Monopolies such as Comcast have no real incentive to upgrade their networks. There is in fact an incentive to not upgrade since a limited commodity commands a higher price than a bountiful one. By limiting bandwidth, Comcast can force Netflix and other providers to pay more or opt into the premium class.

While the eyeball ISPs such as Comcast and Time Warner are monopolistic, the transit ISPs are not and must compete with one another. Any transit ISP that charges higher prices for the same global connectivity as another ISP is going to lose business. As reported by

Vox.com (from data collected from

DrPeering.com),

average transit prices have fallen by a factor of 1000 since 1998, a far different story than what is happening in the world of monopolistic eyeball ISPs.

If customers notice the eyeball ISPs’ failure to upgrade service through slower download speeds, transit ISPs notice it through blocked or over-utilized interchange points. Transit ISPs have long noticed that certain interface points are regularly over-utilized to the point they cannot accept additional traffic and start dropping packets. The interesting point is that blocked interchanges occur only in those markets monopolized or dominated by a single eyeball ISP and nowhere else. Internet exchange points, which are essentially line cards on routers, are not expensive; at a cost of $30,000, they represent a rounding error to Comcast’s daily profits. Adding new interchanges would easily accommodate increased data traffic from Netflix or any other content provider, but for profit reasons such upgrades are resisted. (For more about the perspective from the transit side, see

Observations of an Internet Middleman.)

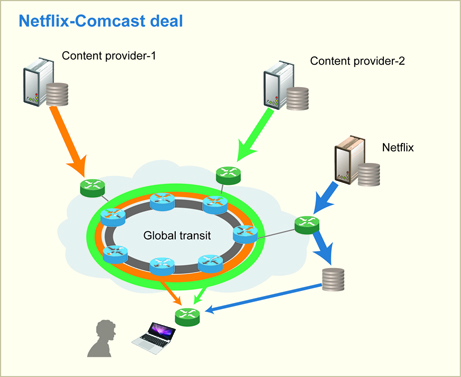

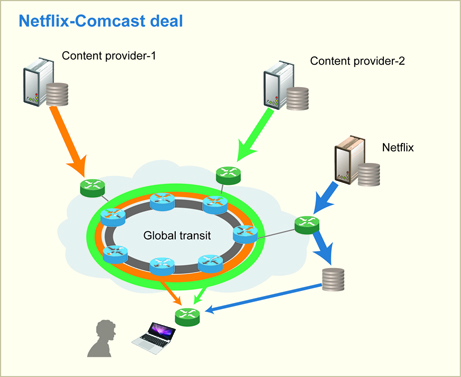

Besides charging more for fast Internet lanes, ISPs have other ways to extract revenues from content providers. What Netflix paid for in its deal with Comcast was not a fast lane in the Internet, but a special arrangement whereby Comcast connects directly to Netflix’s servers to speed up content delivery. It is important to note that this arrangement is not currently covered under conventional net neutrality, which bans fast lanes over the Internet backbone. In the Netflix-Comcast deal, Netflix’s content is being moved along a private connection and never reaches the global Internet. (Tom Wheeler, chairman of the FCC, has acknowledged that these interconnection arrangements do not fall within the scope of any net-neutrality protections.)

According to Misra, net neutrality loses its meaning and becomes irrelevant when ISPs and content providers arrange private pathways that avoid the global links. “Technically you restrict fast lanes on a public highway, but you are freely allowing private highways for paying content providers. The effect is much the same.”

In the face of the monopolistic power of ISPs and their stiff resistance to regulation (which they are increasingly able to avoid in any case) and with perverse incentives to not increase bandwidth, the hope for maintaining a free and open Internet would seem to be a lost cause.

A little competition would help

Susan Crawford, a professor of Law who served as President Barack Obama’s Special Assistant for Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy and author of

Captive Audience, The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age and

The Responsive City, has extensively researched the issue from a legal and consumer perspective. She has been a vocal proponent of municipal broadband, arguing that competition will keep prices in line and improve services. It’s an argument that makes sense and it forms the basis for US anti-trust legislation. But will it work?

According to Ma and Misra, it will. In

The Public Option: A Non-regulatory Alternative to Network Neutrality (originally published 2012) they again use game-theory economics to model how various participants would act in different scenarios, including a monopolistic one regulated by net neutrality as well as a scenario that introduces a public-option ISP.

The mathematical models they built more realistically simulate actual traffic flow on the Internet, taking into account the complexities of TCP, specifically how TCP traffic behaves in congestion. The previous models used by economists had assumed open-loop traffic (i.e., the bandwidth demand of the flows ignore the level of congestion) moving through what is called in queueing theory

an M/M/1 queue. This seemingly sophisticated mathematical model view ignores that TCP is closed loop (meaning it reacts to congestion) and that TCP packets move through a complex network of routers (packets from the same origin might take different paths). Closed- and open-loop traffic flows behave very differently under congestion, and economic models that fail to account for this and other differences often arrive at incorrect conclusions about the quality of service delivered by the network.

Using more sophisticated modeling, Ma and Misra are able to show that even under tightly regulated net-neutrality, monopolies increase their profits when bandwidth is scarce. However, the introduction of a public-option ISP changes the equation. Under a scenario that includes a public-option ISP, profits become tied to market share, thus incentivizing ISPs to increase bandwidth to make themselves more attractive to customers. If the existing ISP employs some non-neutral strategies, consumers have the option to move to a network-neutral public ISP.

According to Crawford “(lack of) competition for high-capacity Internet access is a big issue here in the US. A public-option in the form of municipal fiber is something that I have long advocated as a possible solution to the issue. Vishal’s work validates technically what a lot of us have been arguing for from a policy perspective.”

This is borne out by real-world examples in those cities that have municipal broadband. In Stockholm where the city laid fiber (raising money through municipal bonds), customers have 100 Mbps Internet at one quarter the price of what customers pay in the US for a connection that is 1/10th the speed. And the city makes money. In the UK market, content providers can choose from at least four ISPs that compete for their business. It’s a market where there is plenty of content, prices are low, and speeds are fast, all with zero network neutrality regulations. Zero.

The pattern holds in the US. Susan Crawford uses the example of Santa Monica’s 10-Gbps broadband service City Net, which charges businesses a third of what a private operator would charge.

(A second, important benefit of municipal broadband is ensuring Internet access to low-income families and those in rural areas, populations not well-served by for-profit companies.)

So why aren’t other US cities doing more to promote municipal broadband?

Because the powerful ISPs and their lobbyists have persuaded politicians in 19 states to enact legislation to prohibit public-funded municipal networks, this despite the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which prevents states from blocking any entity looking to provide telecommunications services. The same ISPs that resist regulations needed to enforce net neutrality apparently have no problem with legislation or regulation when it suits their purposes or maintains their monopolistic status.

ISPs like any business entity will always seek and find profits in any scenario. The goal of inserting a public-option ISP is not to deny profits to ISPs but to align the profit motives of broadband ISPs with customer interests. By forcing ISPs to compete for customer subscriptions on the merits of better service and abundant bandwidth, a municipal ISP does just that.

It is a view that the FCC is now coming around to embrace. In

remarks made just recently (October 1), FCC Chairman Wheeler cited the importance of competition and local choice to increase broadband and Internet speed. More than net-neutrality, as the mathematical modeling by Ma and Misra shows, it is competition that will ensure both a free and open Internet and that the US remains competitive in the global, knowledge-based economy.

Posted November 2015

— Linda Crane