Identifying the Potential—and Limitations—of Quantum Computers

PhD student Natalie Parham on finding the power of quantum computing, and community, at Columbia.

PhD student Natalie Parham on finding the power of quantum computing, and community, at Columbia.

Professors are looking for motivated and talented PhD students to join their research teams. These opportunities are ideal for individuals who are passionate about contributing to their field and are looking for dedicated mentorship from leading experts.

Learn more about the doctoral program and admission to the program.

Graduate students from the department have been selected to receive scholarships. The diverse group is a mix of those new to Columbia and students who have received fellowships for the year.

Yangruibo Ding

Yangruibo Ding

Yangruibo Ding is a fourth-year PhD student working with Baishakhi Ray and Gail Kaiser. His research focuses on source code modeling, specifically learning the semantic perspective of software programs to automate software engineering tasks, such as automatic code generation and program analysis. His research has been awarded the IBM PhD Fellowship and the ACM SIGSOFT Distinguished Paper Award.

Ding received an MS in Computer Science from Columbia University in 2019 and a BE in Software Engineering from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China in 2018. In his free time, he enjoys various sports, regularly playing basketball and table tennis, but he is always looking for new sports to try.

Zachary Huang

Zachary Huang

Zachary Huang is a fifth-year PhD student working on database management systems, advised by Eugene Wu. His previous projects involved building interactive dashboards, machine learning systems, and data search tools on top of join graphs. Currently, he is also exploring solutions to data problems with large language models and accelerating query processing with GPUs.

Zachary Huang graduated with a BS degree in Computer Science from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2019. Besides the Google Ph.D. Fellowship, he also received the Columbia Data Science Institute’s Avanessian PhD Fellowship. In his leisure time, he develops video games.

Jeremy Klotz

Jeremy Klotz

Jeremy Klotz is a second-year PhD student who works with Shree Nayar on computational imaging. His research combines the design of cameras and software to solve computer vision tasks.

Klotz graduated with a BS and MS in electrical and computer engineering from Carnegie Mellon University in 2022.

Rafael Sofaer

Rafael Sofaer

Raphael Sofaer is a third-year PhD student in the Software Systems Lab. The focus of his research is software system reliability, dependency management, and reducing the cost of building dependable software. He is co-advised by Junfeng Yang, Jason Nieh, and Ronghui Gu.

Sofaer graduated from New York University with a B.A. in Math and Computer Science in 2015. He bakes bread every week and loves to try new recipes.

Jacob Blindenbach

Jacob Blindenbach

Jacob Blindenbach is a first-year PhD student interested in applied cryptography and designing practical and deployable secure solutions. He will be working with Gamze Gürsoy to design new privacy-preserving protocols for biomedical data, focusing on genomic data.

In May 2022, Blindenbach received a BS with Highest Distinction in Math and Computer Science from the University of Virginia. He is an avid swimmer who placed 19th at Dutch Nationals in the 100m butterfly and enjoys playing ragtime piano.

Charlie Carver

Charlie Carver

Charlie Carver is a sixth-year PhD student working with Zia Zhou on laser-based light communication and sensing in mobile systems and networking.

Carver received an MS in Computer Science from Dartmouth College in 2022 and a BS in Physics from Fordham University in 2018. Charlie won a Best Paper Award at NSDI’20, Best Demo at HotMobile’20, and the Grand Prize at the 2022 Dartmouth Innovation and Technology Festival. While at Fordham, he received the Victor F. Hess Award for the best record of achievement and service in Physics. He loves skiing, sailing, playing guitar, and caring for his two awesome cats.

Gabriel Chuang

Gabriel Chuang

Gabriel Chuang is a first-year PhD student co-advised by Augustin Chaintreau and Cliff Stein. He is generally interested in fairness-oriented algorithm design, especially in the context of social networks and in fairness in redistricting, i.e., identifying and preventing gerrymandering.

Chuang graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a BS in Computer Science in 2022. In his free time, he likes to draw and play board games.

Samir Gadre

Samir Gadre

Samir Gadre is interested in large-scale dataset construction and model training with an emphasis on understanding how model performance improves predictably with better datasets and bigger models. Nowadays, he investigates these interests in the context of multimodal models and language models. He is a fourth-year PhD student advised by Shuran Song.

Gadre graduated from Brown University with a ScB Computer Science in 2018. Before joining Columbia, he worked as a Software Engineer at Microsoft HoloLens.

Toma Itagaki

Toma Itagaki

Toma Itagaki is a first-year PhD student interested in human-computer interaction and mobile computing. He will work with Zia Xhou to develop mobile computing systems and wearable tech that will enable personalized health, wellness, and productivity.

Itagaki graduated in 2023 from the University of Washington with a BS in Neuroscience.

Tal Zussman

Tal Zussman

Tal Zussman is a first-year PhD student working on operating systems and storage systems for cloud computing. He is advised by Asaf Cidon.

Zussman graduated from Columbia University in May 2023 with a BS in Computer Science with Minors in Applied Mathematics and Political Science. He was a C.P. Davis Scholar and received the Department of Computer Science’s Andrew P. Kosoresow Memorial Award for Excellence in Teaching and Service, the Data Science Institute’s Outstanding Course Assistant Award, and the Columbia University Leadership and Excellence Award for Principled Action.

Daniel Meyer

Daniel Meyer

Daniel Mayer is a first-year PhD student advised by David Knowles. His research interests are machine learning and gene regulation, with a focus on understanding polygenic disease.

After receiving a BS in Computer Science from Tufts University in 2018, Meyer worked as a Computational Associate at the Broad Institute for five years. Meyer is a proud dog parent, enjoys talking about Linux, and plays the bassoon.

Sarah Mundy

Sarah Mundy

Sarah is a first-year PhD student advised by Salvatore Stolfo. Her research interests are cybersecurity applied to quantum computing, specifically looking at potential malware attack vectors. Previously, Sarah worked with NASA’s Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer in the workforce planning group, the Pentagon’s Office of the Undersecretary of Defense Research & Engineering under the Principal Director of AI, on DARPA’s Media Forensic program, and with various military and intelligence research groups focused in the AI and ML spaces.

She graduated from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a BS in Electrical Engineering in 2013. She has received the Echostar Spot Award for outstanding performance on a satellite networking project, NAVAIR’s Flight Test Excellence Award for her work planning Tomahawk missile software test flights, the UNR Outstanding Student Service Awards for both the College of Engineering and the Department of Electrical Engineering, 1st and 2nd place in the IEEE Region 6 paper and design competition, respectively, and is a Tau Beta Pi engineering honors society lifetime member.

Her hobbies include running, lifting, hiking, reading science fiction and non-fiction, and caring for her orchids and potted fruit tree.

Argha Talukder

Argha Talukder

Argha Talukder is interested in machine learning in computational biology, specifically modeling the impact of evolutionary genomics on diseases. She is a first-year PhD student advised by Itsik Pe’er and David Knowles.

In 2021, she earned a BS in Electrical Engineering from Texas A&M University, College Station. In her spare time, she learns new languages by watching foreign films.

Max Chen

Max Chen

Max Chen is a third-year PhD student interested in dialogue systems, conversation modeling, and human-centric artificial intelligence. He works with Zhou Yu to develop better models and systems for multi-party conversations and mixed-initiative contexts.

Chen graduated cum laude in 2021 from Cornell University with a BA in Computer Science and BA in Statistical Science. He also received an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship in 2021. He likes to keep active by going for runs and playing various sports like basketball and ultimate frisbee, enjoys listening to all sorts of music, and plays the violin, piano, and ukulele.

Siyan “Sylvia” Li

Siyan “Sylvia” Li

Siyan “Sylvia” Li is a first-year PhD student working on empathetic dialogues in both speech and text modalities and their applications. She is co-advised by Julia Hirschberg and Zhou Yu.

Li completed her BS in Computer Science at Georgia Institute of Technology in 2020 and an MS in Computer Science at Stanford University in 2023. Li enjoys arts and crafts, movies, musicals, and comedy. She is a comedic improviser and is a frequent visitor to Broadway shows.

Jingwen Liu

Jingwen Liu

Jingwen Liu is a first-year PhD student interested in understanding the theoretical properties of current machine learning models and developing algorithms with theoretical guarantees. She is co-advised by Daniel Hsu and Alex Andoni.

Liu graduated summa cum laude with a BS in Mathematics and Computer Science from UC San Diego in 2023. She loves skiing, playing ping pong, and reading fiction in her spare time.

Matthew Beveridge

Matthew Beveridge

Matthew Beveridge is a first-year doctoral student in the CAVE Lab working with Shree Nayar. His research focuses on computer vision, computational imaging, and machine learning for robust perception of the physical environment. Beyond research, Matthew has been involved with startups in the field of autonomy, organized community events around energy and climate, and worked on human spaceflight at NASA. In addition to the Greenwoods Fellowship, he is also a recipient of the LEAP Momentum Fellowship to study the optical properties of atmospheric aerosols.

In 2021, Matthew completed an MEng and BS in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) with a double major in Mathematics and a minor in Theater Arts.

Cyrus Illick

Cyrus Illick

Cyrus Illickis a first-year PhD student co-advised by Vishal Misra and Dan Rubenstein. He is interested in network systems and will do research on fairness and reliability in congestion control protocols.

In 2023, Illick graduated with a BA in Computer Science from Columbia University. He enjoys playing squash and gardening.

Xiaofeng Yan

Xiaofeng Yan

Xiaofeng Yan is a first-year PhD student in the MobileX Lab, advised by Xia Zhou. Her research interests are in human-computer interaction and the Internet of Things, with the aim to design and build mobile sensing systems with better usability.

Xiaofeng earned an MS in Information Networking in 2023 from Carnegie Mellon University. In 2021, she graduated from Tsinghua University with a BS in Automation and a second degree in Philosophy.

After growing up in Jiangsu, China, Sitong Wang studied electrical engineering at Chongqing University and the University of Cincinnati. During her co-op at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), she was introduced to Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). This research area understands and enhances the interaction between humans and computers. She became interested in the field and then took her master’s at Columbia CS. Wang was intrigued by how computation can power the creative process when she worked on a design challenge that blends pop culture references with products or services and helped a group of students promote their beverage start-up.

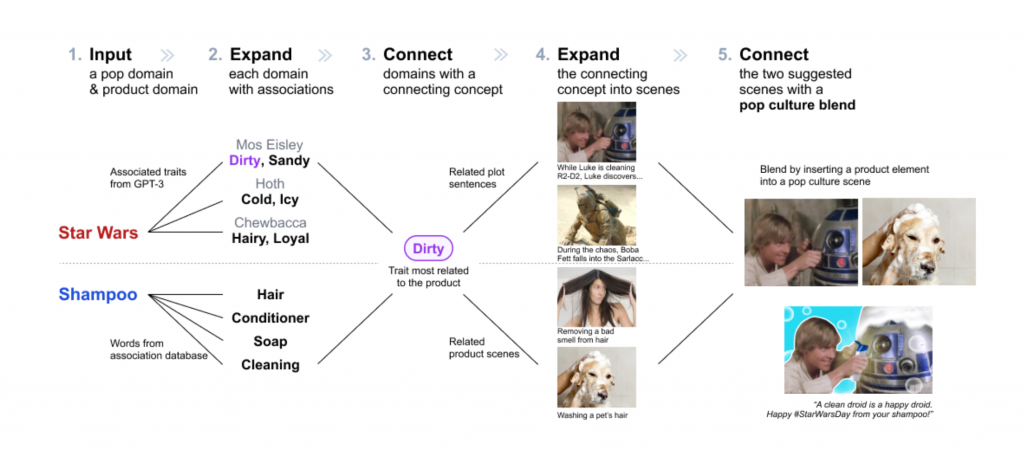

Encouraged by the creative work she could do, Wang joined the Computational Design Lab as a PhD student to continue to work with Assistant Professor Lydia Chilton and explore ways to design AI-powered creativity support tools. She recently published her first first-author research paper at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2023). She and colleagues designed PopBlends, a system that automatically suggests conceptual blends by connecting a user’s topic with a pop culture domain. Their user study shows that people found twice as many blend suggestions as they did without the system and with half the mental demand.

We caught up with Wang to discuss her research, her work on generative AI tools, and what it is like to be a graduate student at Columbia.

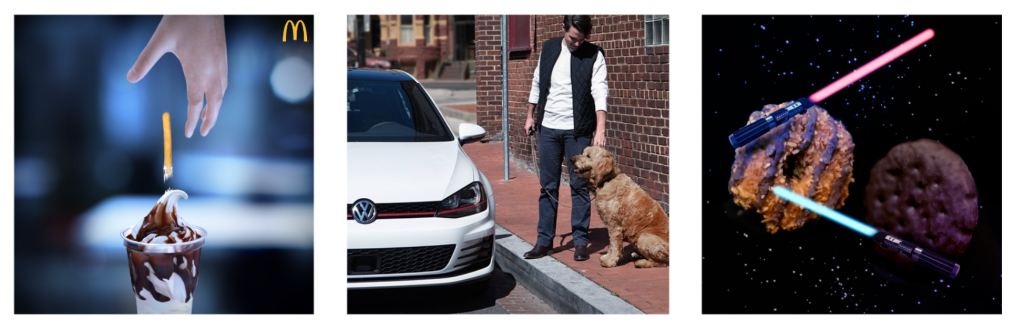

In the paper, we tackled the creative challenge of designing pop culture blends—images that use pop culture references to promote a product or service. We designed PopBlends, an automated pipeline consisting of three complementary strategies to find creative connections between a product and a pop culture domain.

Our work explores how large language models (LLMs) can provide associative knowledge and commonsense reasoning for creative tasks. We also discuss how to combine the power of traditional knowledge bases and LLMs to support creators in their divergent and convergent thinking.

It can help people, especially those without a design background, create pop culture blends more easily to advertise their brands. We want to make the design process more enjoyable and less cognitively demanding for everyone. We hope to enhance people’s creativity and productivity by scaffolding the creative process and using the power of computation to help people explore the design space more efficiently.

Pop culture is important in everyday communication. Pop culture blends are helpful for online campaigns because they capture attention and connect the product to something people already know and like. However, creating these images is a challenging conceptual blending task and requires finding connections between two very different domains.

So we built an automated computational pipeline that can effectively support divergent and convergent thinking in finding such creative connections. We explored how to apply generative AI to creative workflows to assist people better—generative AI is powerful, but it is not perfect—thus, it is valuable to use different strategies that combine a knowledge base (which is accurate) and LLM (which has a vast amount of data) to support creative tasks.

Conceptual blending is complex—the design space is vast and valuable connections are rare—to tackle this challenge, we need to scaffold the ideation process and combine the intelligence of humans and machines. When we started this project, GPT-3 was not yet available; we tried traditional NLP techniques to find attribute associations (e.g., Chewbacca is fluffy) but faced challenges. Then, by chance, we tried GPT-3, which worked well with the necessary prompt engineering.

I was surprised by the associative reasoning capability of LLMs—which is technically a model that predicts the most probable next word. It easily listed related concepts for different domains and could suggest possible creative connections. I was also surprised by the hallucinations the LLMs made through our experiments, and the models could say things that were not true with great confidence.

As an emerging technology, LLMs are powerful in many ways and open up new opportunities for the computational design field. However, LLMs currently have a lot of limitations; it is essential to explore how to build system architectures around them to produce valuable results for people.

I was both nervous and excited because it had been a long time since I had presented in front of a crowd (since we did everything online during COVID). It was also my first time presenting at a computing conference, and the “Large Language Models” session I attended was very popular.

I am grateful to my labmate Vivian Liu, who provided valuable advice, helped me rehearse, and took pictures of me. The presentation went well, and I am glad we had the opportunity to present our work to a large audience of researchers. I would also like to express my gratitude to the researchers I met during the conference, as they provided encouragement and helpful tips that greatly contributed to my experience.

I am working on a tool to help journalists transform their print articles into reels using generative AI by assisting them in the creative stages of producing scripts, character boards, and storyboards. In this work, in addition to LLMs, we incorporate text-to-image models and try to combine the power of both to support creators.

During the summer, I will work as a research intern at Adobe, where I will be focusing on AI and video authoring. Our work will revolve around facilitating the future of podcast video creation.

My undergraduate program offered great co-op opportunities that allowed me to explore different paths, including roles as an engineer, UI designer, and research intern across Chongqing, Charlottesville, and Hong Kong. During my final co-op, I had the opportunity to work in the HCI lab at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST). This experience ignited my passion for HCI research and marked the beginning of my research journey in this field.

I enjoy exploring unanswered questions, particularly those that reside at the intersection of multiple disciplines. A PhD program provides an excellent opportunity to work on the problems that interest me the most. In addition, I think the training provided at the PhD level can enhance essential skills such as leadership, collaboration, critical thinking, and effective communication.

My research interest lies in the creativity support in the HCI field. I am particularly interested in exploring the role of multimodal generative AI in creativity support tools. I enjoy developing co-creative interactive systems to support everyone in their everyday creative tasks.

I want to explore the role of generative AI models in future creativity support tools and build co-creative intelligent systems that support multimodal creativity, especially in the dimensions of audio and videos, as they are how we interact with the world. I also want to explore some theoretical questions, such as the overtrust/overreliance in AI, and see how we might understand and resolve them.

I love the vibrant environment of Columbia and NYC and how Columbia is strong in diverse disciplines, such as journalism, business, and law. It is an ideal place to do multi-disciplinary collaborative research.

Also, I got to know Professor Chilton well during my masters at Columbia. She is incredibly supportive and wonderful, and we share many common interests. That is why I chose to continue to work with her for my PhD journey.

The highlight would be when I witnessed the success of the students I mentored. It was such a rewarding process to guide and help undergraduate students interested in HCI research begin their journey.

Enjoy your time in NYC! Please don’t burn yourself out; learn how to manage your time efficiently. Don’t be afraid to try new things—start with manageable tasks, but also step out of your comfort zone. You will have fun!

If you want to do research, find research questions that genuinely interest you and be prepared to face challenges. Most importantly, preserve and trust yourself and your collaborators. Your efforts will eventually pay off!

The third-year PhD student is creating tools to help people with vision impairments navigate the world.

Imagine walking to your office from the subway station on a Monday morning. You notice a new café on the way, so you decide to take a detour and try a latté. That sounds like a normal way to start the week, right?

But for people with vision impairment or low vision, like those who are categorized as blind and low vision (BLV), this kind of spontaneous exploration while outside is challenging. Current navigation assistance systems (NAS) provide turn-by-turn instructions, but they do not allow visually impaired users to deviate from the shortest path to their destination or make decisions on the fly. As a result, people with vision impairment or low vision often miss out on the freedom to go out and navigate on their own terms.

In a paper published at the ACM Conference On Computer-Supported Cooperative Work And Social Computing (CSCW ‘23), computer science researchers introduced the concept of “Exploration Assistance,” which is an evolution of current NASs that can support BLV people’s exploration in unfamiliar environments. Led by Gaurav Jain, the researchers investigated how NASs should be designed by interviewing BLV people, orientation and mobility instructors, and leaders of blind-serving organizations, to understand their specific needs and challenges. Their findings highlight the types of spatial information required for exploration beyond turn-by-turn instructions and the difficulties faced by BLV people when exploring alone or with the help of others.

Jain, who is advised by Assistant Professor Brian Smith, is a PhD student in the Computer-Enabled Abilities Laboratory (CEAL Lab), where researchers develop computers that help people perceive and interact with the world around them. Their paper presents the results of interviews with BLV people and other stakeholders to identify the types of spatial information BLV people need for exploration and the challenges BLV people face when exploring unfamiliar environments. The paper offers insights into the design and development of new navigation assistance systems that can support BLV people in exploring unfamiliar environments with greater spontaneity and agency.

Based on their findings, they presented several instances of NASs that support the exploration assistance paradigm and identify several challenges that need to be overcome to make these systems a reality. Jain hopes that his research will ultimately enable BLV people to experience greater agency and independence as they navigate and explore their environments. We sat down with Jain to learn more about his research, doing qualitative research, and the thought processes behind writing research papers.

This research is incredibly exciting for the blind and low vision (BLV) community, as it represents a significant step towards equal access and agency in exploring unfamiliar environments. For BLV people, the ability to navigate and explore independently is essential to daily life, and current navigation assistance systems often limit their ability to do so. By introducing the concept of exploration assistance, this research opens up new possibilities for BLV people to explore and discover their surroundings with greater spontaneity and freedom. This research has the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for BLV people and is a major development in the ongoing pursuit of accessibility and inclusion for all.

This was my first project as a PhD student in the CEAL lab. The project was initiated as a camera-based wearable NAS for BLV people, and we conducted several formative studies with BLV people.

As we progressed, we realized that there was a significant research gap in the research community’s understanding of how NASs could support BLV people’s exploration in navigation. Based on these findings, we shifted our focus toward investigating this gap, and the paper I worked on was the result of this pivot. The paper is titled, “I Want to Figure Things Out”: Supporting Exploration in Navigation for People with Visual Impairments.

Over the course of approximately one year, I had the opportunity to work on this project that challenged me to step outside of my comfort zone as a human-computer interaction (HCI) researcher. Before this project, my research experience had primarily focused on computer vision and deep learning. I was more at ease with HCI systems research, which involved designing, building, and evaluating tools and techniques to solve user problems.

This project, however, was a qualitative research study that aimed to gain a deeper understanding of user needs, behaviors, challenges, and attitudes toward technology through in-depth interviews, observations, and other qualitative data collection methods. To prepare for this project, I had to immerse myself in the field of accessibility and navigation assistance for BLV people and read extensively on papers that employed qualitative research methods.

Although it took some time for me to shift my mindset towards qualitative research, this project helped me become a more well-rounded researcher, as I now feel comfortable with both qualitative and systems research. Overall, this project was a significant personal and professional growth experience, as I was able to expand my research expertise and contribute to a worthy cause.

Writing the paper was a critical stage in the research process, and I approached it by first organizing my thoughts and drafting a clear outline. I started by creating an outline of the paper with section and subsection headers, accompanied by a brief summary of what I intended to discuss in each section. This process allowed me to see the overall structure of the paper and ensure that I covered all the essential elements.

Once I had a clear structure in mind, I began to tackle each section of the paper one by one, starting with the introduction and then moving on to the methods, results, and discussion sections. I iteratively refined my writing based on feedback from my advisor, lab mates, and friends.

Throughout the writing process, I also ensured that my writing was clear, concise, and easy to follow. I paid close attention to the flow of ideas and transitions between sections, making sure that each paragraph and sentence contributed to the overall argument and was well-supported by the evidence.

Overall, the process of writing the paper was challenging but rewarding. It allowed me to synthesize the research findings and present them in a compelling way, showcasing the impact of our work on the lives of BLV people.

Throughout the research process, I encountered various challenges that both surprised and tested me. Interviewing participants, in particular, proved to be an intriguing yet difficult task. Initially, I struggled to guide conversations naturally toward my research questions without leading participants toward a certain answer. However, with each interview, I became more confident and began to enjoy the process. Hearing firsthand from BLV people that our work could make a real impact on their lives was also incredibly rewarding.

Analyzing and synthesizing the interview data was another major challenge. Unlike quantitative data, conversations are often open-ended and context-dependent, making it difficult to separate my own biases from the interviewee’s responses. I spent a considerable amount of time reviewing the interview transcripts and identifying emerging themes. To facilitate this process, I leveraged tools like NVivo to better organize the interview data, and our team held several discussions to refine these themes. To ensure the accuracy of our interpretation, we sought feedback from two BLV interns who worked with us over the summer on another project.

Overall, this research experience pushed me to become more adaptable. While it presented its own unique set of challenges, I am proud to have contributed to a project that has the potential to create meaningful change in the lives of BLV people.

Yes, my experience with this research project has certainly changed my view on how to approach research. It has taught me the importance of keeping the paper in mind from the beginning of a project.

Now, I make a conscious effort to think about how I want to present my work and what story I want to tell with the research. This helps me gain more clarity on the direction of the project and how to steer it toward producing meaningful results. As part of my workflow, I now write early drafts of paper introductions even before developing any tools or systems. This allows me to zoom out from the day-to-day technical challenges and see the big picture, which is crucial in making sure that the research is both impactful and well-presented.

Writing a research paper can be a challenging task, but here are a few tips that have helped me make the process smoother:

Finally, one resource that I would totally recommend to every PhD student at Columbia is Adjunct Professor Janet Kayfetz’s class on Technical Writing. Her class is an excellent way to deeply understand research writing.

I am currently working on two exciting projects that further my research goal of developing inclusive physical and digital environments for BLV people. The first project involves enhancing the capabilities of smart streets, streets with sensors like cameras and computing power, to help BLV people navigate street intersections safely.

This project is part of the NSF Engineering Research Center for Smart Streetscapes’ application thrust. The second project is focused on making videos accessible to BLV people by creating high-quality audio descriptions available at scale.

My exposure to research during my undergrad was invaluable, as it allowed me to work on diverse projects utilizing computer vision for various applications such as biometric security and medical imaging. These experiences instilled in me a passion for the research process. It was fulfilling to be able to identify problems that I care about, explore solutions, and disseminate new knowledge.

While I knew I enjoyed research, it was during the summer research fellowship at the Indian Institute of Sciences, where I collaborated with Professor P. K. Yalavarthy in the Medical Imaging Group, that crystallized my decision to pursue a PhD. The opportunity to work in a research lab, lead a project, and receive mentorship from an experienced advisor provided a glimpse of what a PhD program entails. I was excited by the prospect of being able to make a real-world impact by solving complex problems, and it was then that I decided to pursue a career in research.

I am interested in building Human-AI systems that embed AI technologies (e.g., computer vision) into human interactions to help BLV people better experience the world around them. My work on exploration assistance informs the design of future navigation assistance systems that enable BLV people to experience the physical world with more agency and spontaneity during navigation.

In addition to the physical world, I’ve also broadened my research focus to enhance BLV people’s experiences within the digital world. For example, I developed a system that makes it possible for BLV people to visualize the action in sports broadcasts rather than relying on other people’s descriptions of the game.

Accessibility research has traditionally focused on aiding daily-life activities and providing access to digital information for productivity and work, but there’s an increasing realization that providing access to everyday cultural experiences is equally important for inclusion and well-being.

This encompasses various forms of entertainment and recreation, such as watching TV, exploring museums, playing video games, listening to music, and engaging with social media. Ensuring that everyone has equal opportunities to enjoy these experiences is an emerging challenge. My goal is to design human-AI systems that enhance such experiences.

I was drawn to Columbia CS because of the type of problems my advisor works on. His research focused on creating systems that have a direct impact on people’s lives, where evaluating the user’s experience with the system is a key component.

This was a departure from my undergraduate research, where I focused on building systems to achieve high accuracy and efficiency. I found this user-centered approach to be extremely exciting, especially in the context of his project “RAD,” which aimed to make video games accessible to blind gamers. It was a super exciting prospect to be working on similar problems where you can firsthand see how people reacted and benefited from your solutions. This still remains one of the most fulfilling aspects of HCI research for me. In the end, this is what led me to choose Columbia and work with Brian Smith.

The first thing that comes to mind is the people that I have had the pleasure of working with and meeting. I am grateful for the opportunity to learn from my advisor and appreciate the incredible atmosphere he has created for me to thrive.

Additionally, I have been fortunate enough to make some amazing friends here at Columbia who have become a vital support system. Balancing work with passions outside of work has also been important to me, and I am grateful for the chance to engage with student clubs such as the dance team, Columbia Bhangra, and meet some amazing people there as well. Overall, the community at Columbia has been a highlight for me.

One thing that students wanting to do research should know is that research involves a lot of uncertainty and ambiguity. In fact, dealing with uncertainty can be one of the most challenging aspects of research, even more so than learning the technical skills required to complete a project.

In my own experience, staying motivated about the problem statement has been key to powering through those uncertain moments. Therefore, it is important to be true to yourself about what you are really excited about and work on those problems. Ultimately, this approach can go a long way in helping you navigate your time at Columbia and make the most of your research opportunities.

Michelle Zhou (PhD ’99) explains what no-code AI means and presents five inflection points that led to her current work, including the impact of two professors in graduate school who helped her find her direction in AI.

It’s a Friday night at International House and the graduate student residents of the dormitory are gathered to watch Central do Brasil. Andrea Clark-Sevilla is among them and looks forward to immersing herself in the touching story about friendship and finding one’s greater purpose. It is a much-needed break from the busy last semester of her master’s degree.

The past two years have been non-stop for Clark even though she started her graduate career in 2020 at the height of the pandemic. Although she was fully remote, living in Querétaro, Mexico during her first year, she managed to pack in a research project with Senior Lecturer Ansaf Salleb-Aouissi and win a National Institutes of Health contest for it.

The past two years have been non-stop for Clark even though she started her graduate career in 2020 at the height of the pandemic. Although she was fully remote, living in Querétaro, Mexico during her first year, she managed to pack in a research project with Senior Lecturer Ansaf Salleb-Aouissi and win a National Institutes of Health contest for it.

The Decoding Maternal Morbidity Data Challenge aims to promote and advance research on pregnancy and maternal health. For the challenge, the team looked at data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b) and decided to focus on preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication tied to high blood pressure that could lead to maternal and infant death if left untreated. Together with colleagues from Hunter College, their research, On Predicting and Understanding Preeclampsia: A Machine Learning Approach, developed a machine learning model that can predict women at risk of developing preeclampsia.

This was Clark’s first research project and being part of it helped her decide to pursue a PhD. Clark shared that she looked at the opportunity to use the two-year master’s program to explore and see if a research career is for her. “There are so many different ways to do research and chances to do other interesting things at Columbia, that I was hooked!” said Clark, she will begin her PhD in the fall and continue working with Salleb-Aouissi. “I now know for sure that I want to become a researcher and I am looking forward to starting my PhD.”

While many think that having to do meetings over Zoom and not being able to work and collaborate in person is a hindrance to good work, the opposite is true for Clark. Over the summer, she was able to do an internship with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and volunteered as a student instructor at Columbia’s AI4All summer program for high school students, where she was invited by Professor Augustin Chaintreau to lead a class on machine learning. So while doing research remotely from El Paso, Texas she would jump onto Zoom sessions with the AI4All students who were in New York City. Clark admitted she would not have been able to do both if things were in person.

When she isn’t brushing up on her French and German skills or watching a foreign film or two, Clark is working on her final projects and schoolwork and attending meetings to write the research paper for the preeclampsia project. We sat down with Clark to find out more about how she decided to pursue a PhD and her new love of research.

Q: Did you always want to do research and how did you start working with Professor Ansaf Salleb-Aouissi?

I studied math as an undergrad at Cornell, and it was not until rather late in my program that I found out what application field really interested me research-wise. I took a course in dynamical systems and biology, and it was after this that I found that I was passionate about combining biology and computing.

I actually found Professor Salleb-Aouissi through her wonderful and engaging edX course on Artificial Intelligence. After looking into her research areas, I was absolutely convinced that I wanted to work with her and applied to Columbia hoping to get a chance to collaborate with her in some capacity. It was so incredibly fortunate that it happened to work out that she was looking for students to work on a project during my second semester in the program!

Q: What did you work on and what did you like about the research?

I have mostly worked with evaluating different existing methods for interpreting traditional black-box machine learning models. For the NIH challenge, I leveraged a method called Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to determine which feature(s) had the greatest marginal contribution to a model we trained for predicting the incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant women. Using this method, we were able to narrow the cut-off points for high-risk factors, such as body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and some notable placental analytes (proteins and/or hormones generated by the placenta) and show their influence on the model’s ability to predict the incidence of preeclampsia.

This can be useful information to clinicians who wish to monitor their patients based on a more curated set of risk factors and critical ranges for these, as well as organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) who largely set the guidelines for this medical evaluation. Drafting appropriate guiding criteria for such a potentially dangerous condition has the potential to save many women.

Q: What are you working on now?

We are currently preparing the paper related to the NIH challenge for publication. Our team that worked on this challenge had so many great ideas, and the paper is slowly but surely evolving to its final form. The challenge itself felt rather short-lived, given how rich the data is and the different angles to approach the problem, depending on how one defines preeclampsia, for instance. All these details need to be properly addressed and defended, which takes much time. I am also finishing up my course requirements to graduate.

Q: Why did you decide to get a master’s degree instead of applying for a PhD?

For me, it was very important to figure out if I was suited to doing research before committing to a five-year program in which I would be doing this exclusively. I have heard stories about students dropping out of their PhD programs because it was not what they were thinking they signed up for. I don’t think the traditional undergraduate curriculum adequately prepares one for research, or at least it was not the case for me.

Q: What do you think people should know about doing a master’s degree? If you didn’t go through the program would you have applied for a PhD program?

A master’s degree is a great option if your undergraduate degree is not well-aligned with your career objectives, as it can give you the opportunity to pivot your skillset accordingly. I would say my experience is not the normal use-case for it, as I purely pursued the master’s degree to decide if I enjoyed doing research and could see myself continuing in a PhD program. If I did not enjoy it at all, two years is not a lot of sacrifice career-wise, and it is certainly a good learning experience.

The same cannot be said for a PhD program. I personally would not have had the confidence to commit to a PhD program not having the research experience I had with Professor Salleb-Aouissi. It is a bit of a double risk with a PhD program. First, you need to be reasonably committed to your research topic, and second, and I think most importantly, you need to be confident that you can work well with your advisor.

I feel that many students go into a PhD blindly, straight after undergrad. I am extremely fortunate to be able to say that I am very confident about both thanks to my experience in the master’s program.

I was also lucky enough to win a National GEM Consortium Fellowship for the master’s program. The fellowship allowed me to focus primarily on my research and not have to worry about the financial aspects of being in the program. I was also awarded this fellowship to continue funding my PhD studies.

Q: Why did you decide to apply for a PhD?

I feel that I am very driven when I have control over the questions that I want to answer and I have the freedom to explore them in the ways I see fit. I think that the most suited profession for someone with these characteristics is research.

Doing a PhD gives you the freedom to live in your own little world for five years and come out an expert in what you are passionate about. It’s really a dream situation!

Q: What will be your research focus?

I will continue my research on explainable artificial intelligence, likely in the precision medicine field. I also hope to be able to dig more into the theoretical underpinnings of more statistics-driven approaches and develop my own approaches for interpreting machine learning models.

Q: What sort of research questions or issues do you hope to answer?

I would like to bring the issue of creating explainable AI more to the forefront in the machine learning community. I feel that there is a lot more focus on developing the most state-of-the-art models in terms of predictive performance, but there is not enough research being done to make the results of such models understandable to the end-user, which might very well have serious social impacts.

Q: What is your advice to students on how to navigate their time at Columbia? If they want to do research what should they know or do to prepare?

I think students should take classes that truly interest them, and if possible, also explore courses in other related departments. I have a friend who is taking a project-based course combining data science and climate change, and he is learning so much from it and enjoying it greatly!

I personally think that the best incarnation of learning comes from working on a tangible project like that and having the space to try ideas and explore. That is how it started with me and Professor Salleb-Aouissi.

Q: Is there anything else that you think people should know?

Don’t be afraid to fail at something at first! I always felt pressured to get something right on the first attempt, and I quickly realized that this mentality is not sustainable in the long run if you do research.

You learn so much more from your mistakes than from your successes. Your critical thinking skills are actively engaged when you have to analyze why something failed as compared to when it happily worked on the first try. I would hazard to say that researchers are skilled puzzlers because they always manage to pick up the pieces when something breaks.

“So, this is a rough idea for modeling trajectories and I need your feedback,” said Didac Suris to the room while his teammates looked at him over bowls of Chinese food. “I literally just thought of this two days ago.”

It is the first week that working lunch meetings can resume at Columbia. Suris, along with other members of the computer vision lab, immediately took advantage of it. As they settle down into the meeting, Suris talks about his research proposal and his audience exchanges ideas with him in between bites of food. The last time this happened was two years ago.

“We came back in the Fall and it is good to be back in the office,” said Didac Suris, a third-year PhD student advised by Carl Vondrick. “Collaborating with teammates and just being out has worked wonders for my productivity which has skyrocketed compared to when working alone, or from home.”

Suris can be found in an office in CEPSR working on research projects that study computer vision and machine learning. The projects focus on training machines to interact and observe their surroundings, including his work on predicting what will happen next in a video. This is in line with his long-term goal of creating systems that can model video more appropriately and help predict the future actions of a video, which will be useful in autonomous vehicles, human-robot interaction, broadcasting of sports events, and assistive technology.

Suris was recently named a Microsoft Research Fellow. The research he has done while at Columbia focuses on computer vision and building systems that can learn on their own, which is very different from what he studied in undergrad, telecommunications at the Polytechnic University of Catalunya in Barcelona, Spain. We caught up with Suris to ask about how his PhD is going and winning the fellowship.

Q: What was your journey to Columbia? How did you pivot from telecommunications to applying for a PhD in computer vision?

It was only during my master’s, when I started doing research on computer vision, that I started to consider doing a PhD. The main reason I’m doing a PhD is because I believe it is the best way to push myself intellectually.

I really recommend doing research in different places before starting a PhD. Before starting at Columbia, I did research at three different universities, which prepared me for my current research. These experiences helped me to 1) understand what research is about, and 2) understand that different research groups work differently, and get the best out of each one.

Q: What drew you to machine learning and artificial intelligence?

One of the characteristic aspects of this field is how fast it is evolving, and how impressive the research results have been in the last decade. I don’t think there was a specific moment where I decided to do research on this topic, I would say there was a series of circumstances that led me here, including the fact that I was originally interested in artificial intelligence in the first place, of course.

Q: Why did you decide to focus on computer vision?

There is a lot of information online because of the vast amount of videos, images, text, audio, and other forms of data. But the thing is the majority of this information is not labeled clearly. For example, we do not have information about the actions taking place in every YouTube video. But we can still use the information in the YouTube video to learn about the world.

We can teach a computer to relate the audio in a video to the visual content in a video. And then we can relate all of this to the comments on the YouTube video to learn associations between all of these different signals, and help the computer understand the world based on these associations. I want to be able to use any and all information out there to develop systems that will train computers to learn with minimal human supervision.

Q: What sort of research questions or issues do you hope to answer?

There is a lot of data about the world on the Internet – billions of videos are recorded every day across the world. My main research question is how can we make sense of all of this raw video content.

Q: What was the thesis proposal that you submitted for the Microsoft PhD?

The proposal was called “Video Hyperboles.” The idea is to model long videos (most of the literature nowadays is on very short clips, not long-format videos) by modeling their temporal hierarchy. For example, the action of “cutting an onion” is composed of the subactions “grabbing a knife”, “pressing the knife”, “gathering the pieces.” This forms a temporal hierarchy, in which the action “cutting an onion” is higher in the hierarchy, and the subactions are lower in the hierarchy. Hierarchies can be modeled in a geometric space called Hyperbolic Space, and thus the name “Video Hyperboles.”

I have not been working on the project directly, but I am building up pieces to eventually be able to achieve something like what I described in the proposal. I work on related topics, with the general direction of creating a video representation (for example, a hierarchy) that allows us to model video more appropriately, and helps us predict the future of a video. And I will work on this for the rest of my PhD.

Q: What is your advice to students on how to navigate their time at Columbia? If they want to do research what should they know or do to prepare?

Research requires a combination of abilities that may take time to develop: patience, asking the right questions, etc. So experience is very important. My main advice would be to try to do research as soon as possible. Experience is very necessary to do research but is also important in order to decide whether or not research is for you. It is not for everyone, and the sooner you figure that out, the better.

Q: Is there anything else that you think people should know about getting a PhD?

Most of the time, a PhD is sold as a lot of pain and suffering, as working all day every day, and being very concerned about what your advisor will think of you. At least this is how it is in our field. It is sometimes seen as a competition to be a great and prolific researcher, too. And I don’t see it like that – you can enjoy (or hate) your PhD the same way you enjoy any other career path. It is all about finding the correct topics to work on, and the correct balance between research and personal life.

A group of PhD students wants to reduce the inequities in the department’s PhD application process. They will help applicants of the PhD program – by lending their expertise by reviewing a personal statement. This initiative, called the Pre-Submission Application Review (PAR) Program, is in its second year.

“It is clear that students from underrepresented groups may further benefit from mentorship through the entirety of the process of applying, to deciding, to ultimately entering grad school,” said Sam Fereidooni, a first-year PhD student and PAR Program coordinator. The group plans to organize further mentorship opportunities in future iterations of the program such as spaces where students can engage in conversations in a supportive community of their peers, in addition to current PhD students and faculty members.

“Ultimately, we are trying to provide resources to support underrepresented people in CS, with the goal of addressing inequality in representation,” said Samir Gadre, a 2nd-year PhD student and PAR Program coordinator. The group sees the importance of continuing the program because the status quo does not change quickly. It is a feeling that is shared with other universities – Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology students started similar programs in 2020 as well. Said Gadre, “We feel that PAR programs across the country are a good first step. However, we also recognize that more student and faculty activism, particularly from people in positions of power, is necessary to create meaningful institutional change.”

“Ultimately, we are trying to provide resources to support underrepresented people in CS, with the goal of addressing inequality in representation,” said Samir Gadre, a 2nd-year PhD student and PAR Program coordinator. The group sees the importance of continuing the program because the status quo does not change quickly. It is a feeling that is shared with other universities – Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology students started similar programs in 2020 as well. Said Gadre, “We feel that PAR programs across the country are a good first step. However, we also recognize that more student and faculty activism, particularly from people in positions of power, is necessary to create meaningful institutional change.”

By continuing the program the group hopes to address the systemic disadvantages people from underrepresented communities face by lending a hand and giving advice on how to write a personal statement that will stand out and get the attention of professors.

“Above all applicants must do research on potential faculty that they would like to work with,” said Kahlil Dozier, a 2nd-year PhD student and PAR Program coordinator. Even if an applicant is not completely sure what their intended research area is, it is better to mention specific faculty that may align with their interests in their application. This is one of the most critical pieces of advice; an application will likely get referred to the names mentioned, and those professors may be the ones deciding if the applicant is a suitable candidate for admission.

And it is not enough to just mention the faculty in the application–potential students should actually look at the recent work faculty has done and read their papers. A PhD can take five to seven years to complete so applicants should see if it is the type of work they actually want to dedicate their graduate research career to. Continued Dozier, “If you have done this, it will inevitably come through in your personal statement and bolster your application.”

Here are more points applicants should consider before writing a Personal Statement:

– The Personal Statement is a key part of the application; oftentimes, it is where an applicant can differentiate themself from other applicants

– In short, the intent is to build a personal narrative, goals, and aspirations, and offer a perspective that is fundamentally absent from a resume/CV.

– The application is constrained by limited space, so applicants need to focus on a few concrete experiences (broadly defined) that may have shaped the trajectory of the applicant’s academic career up until this point or even themself as a researcher.

– Even though it is separate and serves a different function than the Research Statement of Purpose, research can still be involved. One approach to making a personal statement is to make a narrative out of one’s CV, fill in the “between the lines”.

– Again, doing prior research on potential faculty can shine through here, and it would be advantageous to show in any way how a faculty member’s work may align with the applicant’s background and goals.

Interested applicants have to apply to the PAR program and submit their personal statement and CV by November 7th at 11:59 pm EST. Because the program is student-run and dependent on volunteers, there is no guarantee that every applicant can be accommodated. Those who are accepted will be notified by November 14th, then paired with a PhD student in the same research area who will review their materials and provide feedback to them by November 21st – well ahead of the December 15th deadline to apply to the PhD program.

Published October 29, 2021

Giannis Karamanolakis, a natural language processing and machine learning PhD student, talks about his research projects and how he is developing machine learning techniques for natural language processing applications.

Can you talk about your background and why you decided to pursue a PhD?

I used to live in Greece and grew up in Sitia, a small town in Crete. In 2011, I left my hometown to study electrical and computer engineering at the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA).

At NTUA, taking part in machine learning (ML) research was not planned but rather a spontaneous outcome stemming from my love for music. The initial goal for my undergraduate thesis was to build an automatic music transcription system that converts polyphonic raw audio into music sheets. However, after realizing that such a system would not be possible to develop in a limited amount of time, I worked on the simpler task of automatically tagging audio clips with descriptive tags (e.g., “car horn” for audio clips where a car horn is sound). Right after submitting a new algorithm as a conference paper, I realized that I love doing ML research.

After NTUA, I spent one and a half years working as an ML engineer at a startup called Behavioral Signals, where we trained statistical models for the recognition of core emotions from speech and text data. After a few months of ML engineering, I found myself spending more time reading research papers and evaluating new research ideas on ML and natural language processing (NLP). By then, I was confident about my decision to pursue a PhD in ML/NLP.

What about NLP did you like and when did you realize that you wanted to do research on it?

I am fascinated by the ability of humans to understand complex natural language. At the moment of writing this response, I submitted the following 10-word query to Google: “when did you realize that you wanted to do research” by keeping quotation marks so that Google looks for exact matches only. Can you guess the number of the documents returned by Google that contain this exact sequence of 10 words?

The answer that I got was 0 (zero) documents, no results! In other words, Google, a company with huge collections of documents, did not detect any document that contains this specific sequence of words. Sentences rarely recur but humans easily understand the semantics of such rare sentences.

I decided to do research on NLP when I realized that current NLP algorithms are far away from human-level language understanding. As an example back from my time at Behavioral Signals, emotion classifiers were misclassifying sentences that contained sarcasm, negation, and other complex linguistic phenomena. I could not directly fix those issues (which are prevalent beyond emotion classification), which initially felt both surprising and frustrating, but then evolved into my excitement for research on NLP.

Why did you apply to Columbia and how was that process?

The computer science department at Columbia was one of my top choices for several reasons, but I will discuss the first one.

I was excited to learn about the joint collaboration between Columbia University and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), on a project that aims to understand user-generated textual content in social media (e.g., Yelp reviews, tweets) for critical public health applications, such as detecting and acting on foodborne illness outbreaks in restaurants. I could see that the project would offer the unique opportunity to do research in ML and NLP and at the same time contribute to this important public application in collaboration with epidemiologists at DOHMH. Fortunately, I have been able to work on the project, advised by Professor Luis Gravano and Associate Professor Daniel Hsu.

Applying to Columbia and other American universities was quite a stressful experience. For many months, my days were filled with working for Behavioral Signals, studying hard for high scores in GRE and TOEFL exams (both of which were required at that time by all US universities), creating a short CV for the first time, and writing a distinct statement-of-purpose for each university. I am glad to observe the recent promising changes in the PhD application procedure for our department, such as waiving the GRE requirements and offering the Pre-submission Application Review (PAR) program, in which current PhD students help applicants improve their applications. (Both of which I would have liked to have been able to take advantage of.)

What sort of research questions or issues do you hope to answer?

My research in the past few years focuses on the following question: Can we effectively train ML classifiers for NLP applications with limited training data using alternative forms of human supervision?

An important limitation of current “supervised ML” techniques is that they require large amounts of training data, which is expensive and time-consuming to obtain manually. Thus, while supervised ML techniques (especially deep neural networks) thrive in standard benchmarks, it would be too expensive to apply to emerging real-world applications with limited labeled data.

Our work attempts to address the expensive requirement of manually labeled data through novel frameworks that leverage alternative, less expensive forms of human supervision. In sentiment classification, for example, we allow domain experts to provide a small set of domain-specific rules (e.g., “happy” keyword indicates positive sentiment, “diarrhea” is a symptom of food poisoning). Under low-resource settings with no labeled data, can we leverage expert-defined rules as supervision for training state-of-the-art neural networks?

For your research papers, how did you decide to do research on those topics? How long did it take you to complete the work? Was it easy?

For my first research project at Columbia, my goal was to help epidemiologists in health departments with daily inspections of restaurant reviews that discuss food poisoning events. Restaurant reviews can be quite long, with many irrelevant sentences surrounding the truly important ones that discuss food poisoning or relevant symptoms. Thus, we developed a neural network that highlights only important sentences in potentially long reviews and deployed it for inspections in health departments, where epidemiologists could quickly focus on the relevant sentences and safely ignore the rest.

The goal behind my next research projects was to develop frameworks for addressing a broader range of text-mining tasks, such as sentiment analysis and news document classification, and for supporting multiple languages without expensive labeled data for each language. To address this goal, we initially proposed a framework for leveraging just a few domain-specific keywords as supervision for aspect detection and later extended our framework for training classifiers across 18 languages using minimal resources.

Each project took about 6 months to complete. None of them were easy; each required substantial effort in reading relevant papers, discussing potential solutions with my advisors, implementing executable code, evaluating hypotheses on real data, and repeating the same process until we were all satisfied with the solutions and evaluation results. The projects also involved meeting with epidemiologists at DOHMH, re-designing our system to satisfy several (strict) data transfer protocols imposed by health departments, and overcoming several issues related to missing data for training ML classifiers.

Your advisors are not part of the NLP group, how has that worked out for you and your projects?

It has worked great in my humble opinion. For the public health project, the expertise of Professor Gravano on information extraction, combined with the expertise of Professor Hsu on machine learning, and the technical needs of the project have contributed without any doubt to the current formulation of our NLP-related frameworks. My advisors’ feedback covers a broad spectrum of research, ranging from core technical challenges to more general research practices, such as problem formulation and paper writing.

Among others, I appreciate the freedom I have been given for exploring new interesting research questions as well as the frequent and insightful feedback that helps me to reframe questions and forming solutions. At the same time, discussions with members of the NLP group, including professors and students, have been invaluable and have clearly influenced our projects.

What do you think is the most interesting thing about doing research?

I think it is the high amount of surprise it encompasses. For many research problems that I have tried to tackle, I started by shaping an initial solution in my mind but in the process discovered surprising findings that undoubtedly changed my way of thinking – such as that my initial solution did not actually work, simpler approaches worked better than more sophisticated approaches, data followed unexpected patterns, etc. These instances of surprise turned research into an interesting experience, similar to solving riddles or listening to jazz music.

Please talk about your internships – the work you did, how was it, what did you learn?

In the summer of 2019, I worked at Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle with a team of more than 15 scientists and engineers. Our goal was to automatically extract and store knowledge about billions of products in a product knowledge graph. As part of my internship, we developed TXtract, a deep neural network that efficiently extracts information from product descriptions for thousands of product categories. TXtract has been a core component of Amazon’s AutoKnow, which provides the collected knowledge for Amazon search and product detail pages.

During the summer of 2020, I worked for Microsoft Research remotely from New York City (because of the pandemic). In collaboration with researchers at the Language and Information Technologies team, we developed a weak supervision framework that enables domain experts to express their knowledge in the form of rules and further integrates rules for training deep neural networks.

These two internships equipped me with invaluable experiences. I learned new coding tools, ML techniques, and research practices. Through the collaboration with different teams, I realized that even researchers who work on the same subfield may think in incredibly different ways, so to carry out a successful collaboration within a limited time, one needs to listen carefully, pre-define expected outcomes (with everyone in the team), and adapt fast.

Do you think your skills were improved by your time at Columbia? In which ways?

Besides having improved my problem-finding and -solving skills, I have expanded my presentation capabilities. In the beginning, I was frustrated when other people (even experienced researchers) could not follow my presentations and I was worried when I could not follow other presenters’ work. Later, I realized that if (at least part of) the audience is not able to follow a presentation, then the presentation is either flawed or has been designed for the wrong audience.

Over the past four years, I have presented my work at various academic conferences and workshops, symposiums at companies, and student seminars, and after having received constructive feedback from other researchers, I can say that my presentation skills have vastly improved. Without any doubt, I feel more confident and can explain my work to a broader type of audience with diverse expertise. That said, I’m still struggling to explain my PhD topic to my family. 🙂

What has been the highlight of your time at Columbia?

The first thing that comes to mind is the “Greek Happy Hour” that I co-organized in October 2019. More than 40 PhD students joined the happy hour, listened to Greek music (mostly “rempetika”), tasted greek specialties (including spanakopita), and all toasted loudly by saying “Γειά μας” (ya mas; the greek version of “cheers”).

Was there anything that was tough to handle while taking your PhD?

It is hard to work from home during a pandemic. A core part of my PhD used to involve multi-person collaborations, drawing illustrations on the whiteboards of the Data Science Institute, random chats in hallways, happy hours, and other social events. All these have been harder or impossible to retain during the pandemic. I miss it and look forward to enjoying it again soon.

Looking back, what would you have done differently?

If I could, I would have engaged in more discussions and collaborations, taken more classes, played more music, and slept less. 🙂

What is your advice to students on how to navigate their time at Columbia? If they want to do NLP research what should they know or do to prepare?

They should register for diverse courses; Columbia offers the opportunity to attend courses from multiple departments. They should reach out to as many people as possible and do not hesitate to email graduate students and professors. I love receiving emails from people that I haven’t met before, some of which stimulated creative collaborations.

For those that want to do NLP research (which I highly recommend–subjectively speaking), you should contact me or any person in the NLP group.

What are your plans after Columbia?

I plan to continue working on research, either as a faculty member or in an industry research and development department.

Is there anything else that you think people should know?

Columbia offers free and discounted tickets to museums and performances around New York City, even virtual art events. I personally consider New York as the “state-of-the-art”.